we’re going

to build a

better

world

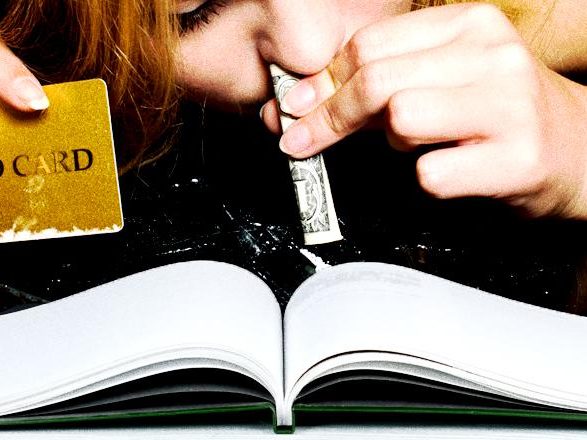

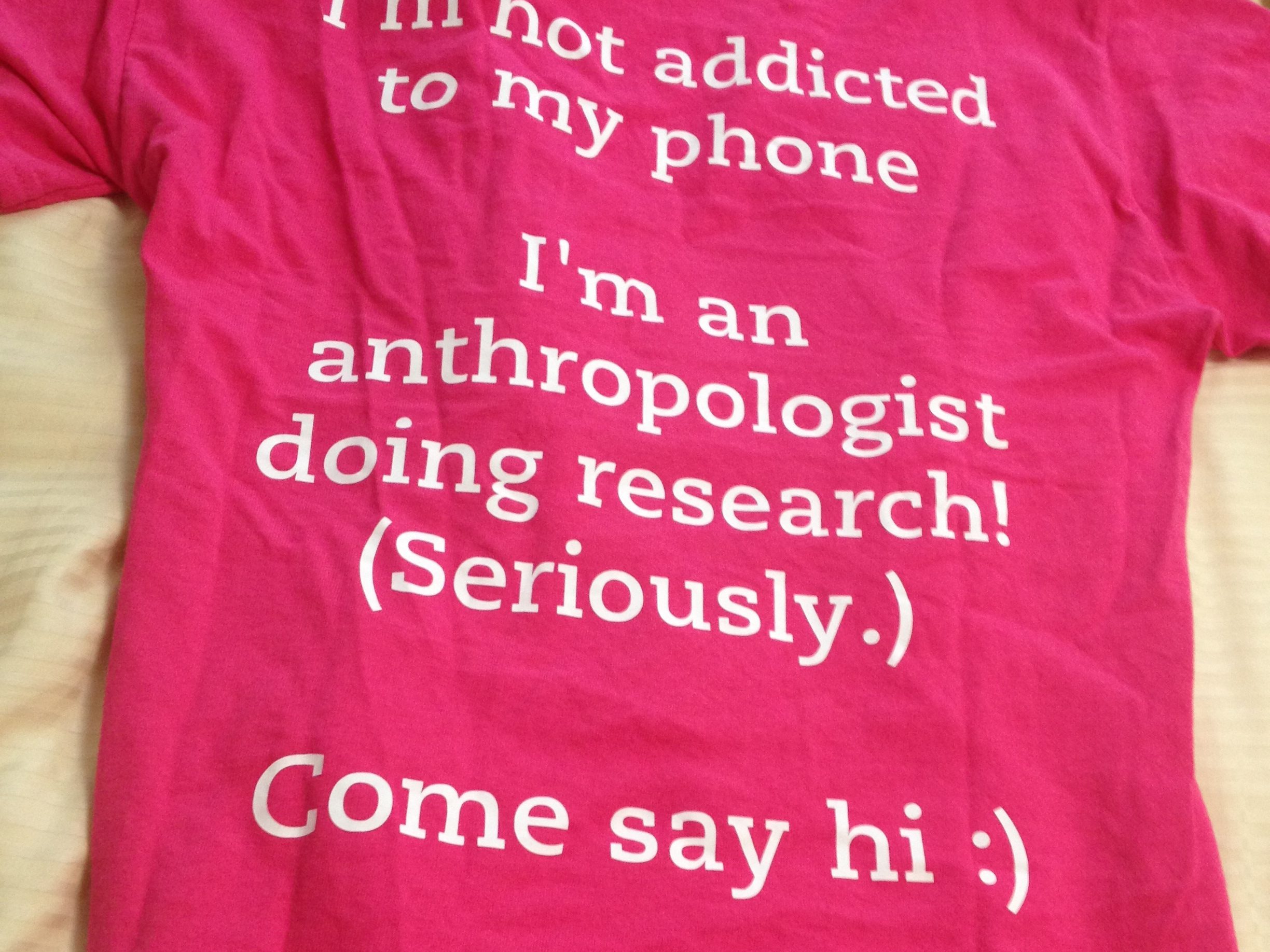

Hi, I’m Dr. Hilary Agro. I’m an anthropologist who does public education about how we can work together to build a world that isn’t run by soulless billionaires, where everyone is valued and taken care of. I also teach on the subjects of drugs/plant medicines (especially psychedelics), harm reduction, collective healing, abolition, and conflict transformation.

My work is here on my website, as well as on Bluesky, TikTok, and Instagram. Support my work, and my kids, on Patreon!

My work

Work collaboratively with me to set your journey up for success. All funds go to support my research and organizing work.