Leftists, because on the whole we are mostly (and rightfully) not all that excited about AI as it exists today, are often accused of being luddites or of hating technology.* But no, I do like some technology. I’m not against it as a concept. We perfected textiles 4,000 years ago. Then we invented books, and vaccines, and those kick ass. But almost everything else has been based on environmental destruction and labour exploitation, “solving” “problems” that only exist because of colonialism.

So no, I don’t like the robots. Fight me. Or: try to understand me.

When we’re faced with these accusations, I sometimes see people say “hey, we love technology! We love high speed rail and mRNA vaccines!” And sure, we can take their bait and remain always on the defense, having conversations on their terms. But we also absolutely do not have to fall over ourselves saying that we love technological progress. The onus is on the Tech Bros to explain to us why we should be excited about new technology while there are microplastics in every mother’s breast milk and our rivers are drying up. And that’s what we should be hammering home in all of these conversations. Colonizers answer the question of “what are you going to do with this mass produced product when its usable lifespan is up to ensure it doesn’t poison our children’s environment” challenge, difficulty level: impossible.

However, this is a wedge subject that I don’t think leftists are having enough hard conversations about. I have close friends for whom so much of their comfort, even their creativity, is based in electronic tech that some don’t really seem able to take a sincere, hard look at the environmental and social consequences of a screen-based society at scale, or at what it might be doing to us to let our joy be mediated by products we’re being sold.

Adding even more discomfort to the situation, this issue connects directly with the other two major wedge issues that are deeply unresolved on the left, which are:

- Land back: The return of all land to indigenous stewardship.

- Child liberation: The prioritization of the well-being of children, those living now and those to come, in every aspect of society and our daily lives.

I for one, do not find it acceptable that in Canada we churn through plastic at an appalling rate because we’re too exhausted and depressed to cook or sew, and then we send our garbage to choke the air and waters of children in Malaysia. I do not like that.

I don’t think that children in Vietnam deserve to bear the cost of the addiction to immediate gratification that we’ve been given as a trickle-down result of our overlords’ addiction to power and domination.

I don’t think it’s acceptable that we want new gaming systems, so they get poisoned.

Whenever I’m speaking with a tech-optimist liberal or leftist who is suggesting solutions that require the maintenance of, or expansion of, personal devices or computer-based infrastructure (e.g., a new game that teaches people about empathy, or an app that helps people find better housing, or any pro-social use of AI), I cautiously ask some version of these questions: “If your solution requires more technology to be manufactured, what should we do with it when it breaks, to ensure it doesn’t poison the environment? Can we focus on building the recycling infrastructure first to handle more production, before we make new stuff? Whose lands will be mined for the resources? Whose water will be used?”

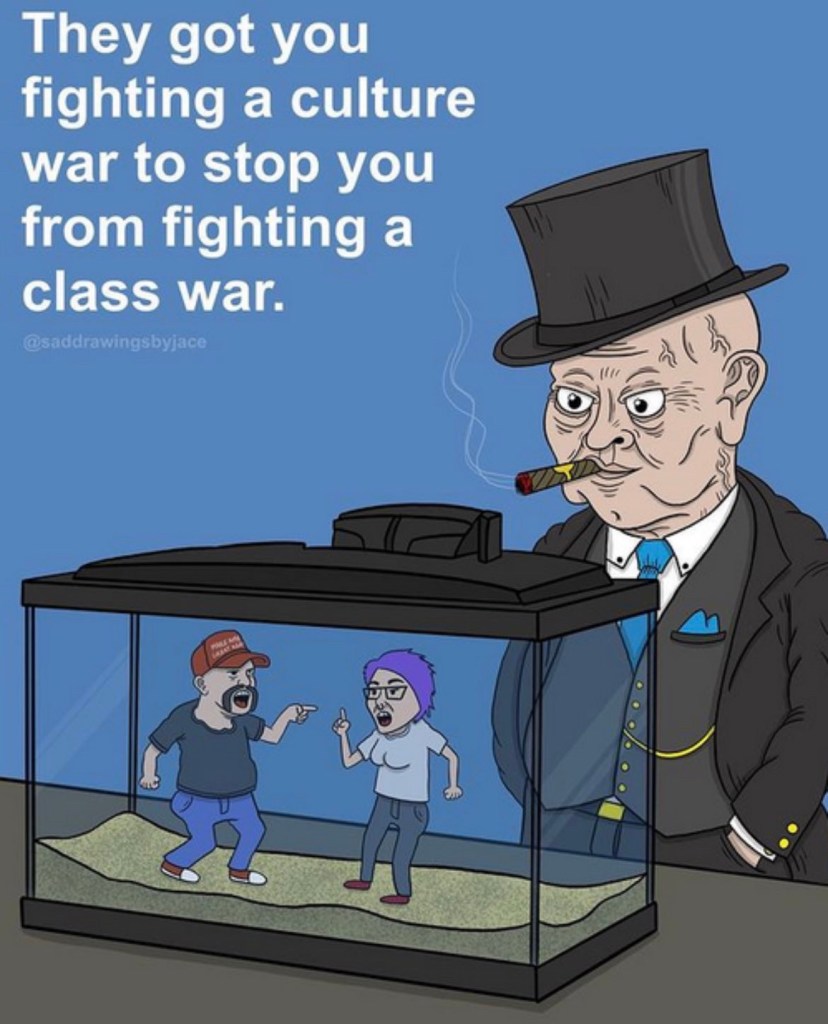

When I try to talk about this, some people shut down. They downplay and dismiss, and use thought-terminating cliches like “well we can’t just go back to living in caves.” And I don’t even blame them for not wanting to think about it. Disconnected as we are from the earth, from each other, from ritual and song and tradition and children and elders, we have so little that makes us happy. Capitalism gave us little emotion-regulation boxes made by slaves and we were in too much generational pain to think about the consequences of outsourcing our emotional stability to the slave boxes, so now the thought of losing our phones causes more distress in our bodies than a tree being cut down in our neighbourhood or a shipment of electronic waste heading for Indonesia. And as AI companies offer yet another “solution” to our collective alienation—don’t worry about why it’s so difficult to find someone who understands you, just become dependent on the robot, it’ll always be nice to you!—we are too ungrounded from the earth to see that AI is not revolutionary, it’s not a game changer, it’s just more of the same transmutation of the earth’s resources into dissociation from centuries of colonial trauma. We are collectively making out with a gun to feel better. We are being sold more poison as a cure for the poison.

This is why all my organizing work comes back to healing. We are too traumatized to be in real solidarity with the global south. We cannot actually have rational debates about technology, because our ability to reason is compromised by the fantasy world we live in where the material consequences of our actions don’t exist where we don’t see them. We need to fix our inner shit for those conversations to even be possible. I simply don’t really trust any opinion about the value of technological “progress” that comes from someone addicted to the fruits of capitalist technological progress, any more than I trust a billionaire’s opinion about money or a gambler’s opinion about casinos. If you can’t imagine life without your computer, then you’d better start imagining life where electronics are not produced through exploitation and Congo has complete sovereignty over their mineral production, so we can bring that world into reality.**

As it stands, as long as we’re still clinging to mass-produced trinkets for our sense of stability, we will prioritize those coping mechanisms over the well-being of the world’s children. As long as we rely on screens rather than on forests and sunsets to soothe us, we will fight to defend the screens, not the forests. Whatever you get your comfort from, that is what you will fight to defend.

If AI is your friend and therapist, maintaining that “relationship” is what you are going to centre in these struggles. If screens are our ultimate solace, we’ll let the forests burn. We’re doing it right now. The machine is churning to feed us.

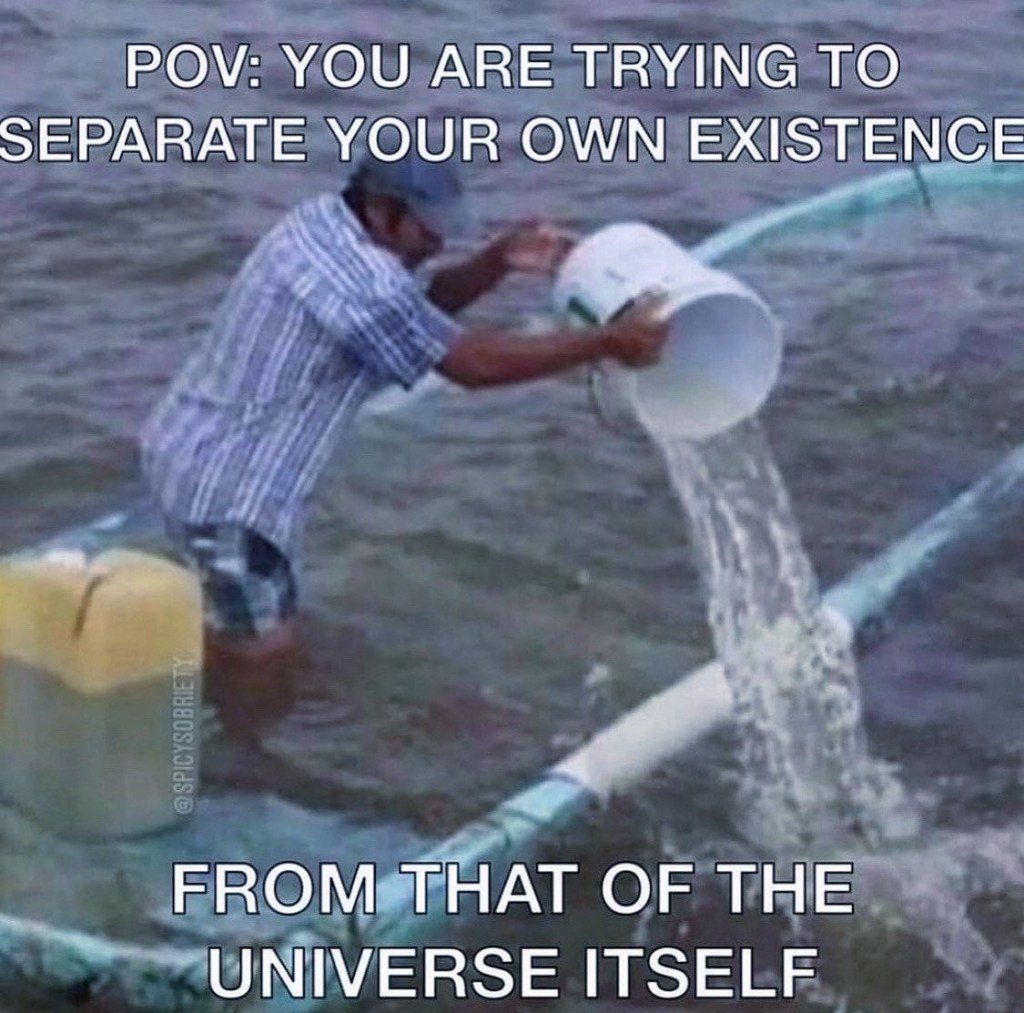

We have got to divest from these poisoned crutches, beloveds. I am included in this as well. It’s been my primary motivation and compass for generational healing over the last decade: to root my sense of self, the groundedness and love and compassion that all my activism and caregiving come from, within nature, the elements, and nature-based spirituality. Nature, the source that unites us all as living creatures on this earth, is the only thing that’s always there for us. Nature will not break up with you, nature will not call the cops on you. Nature will not leave you without entertainment when the wifi isn’t working, she will never lie to or gaslight or manipulate you. Mother Earth is pissed right now, but she will never abandon us, and she will not die before we do. She will be alive as long as you are, because your life depends on hers. She is the only truly safe attachment, the only comfort that is always, always there for us. Those of us who are settlers and immigrants and renters and workers have had our connection to the Earth, our secure attachment, severed, and we’ve been doing a Domination about it for centuries: suffering and looting and pillaging and fighting, trying to fill the void in our hearts that started with internal European colonization and separation from the animist spirituality and philosophies of our ancestors (the ones that lived sustainably with their environment, not the later ones that burned each other at the stake for saying the exact same things I’m saying right now. I know that much of what I’ve said here is probably deeply uncomfortable, so thanks for engaging with it instead of sending an inquisition after me, babes).

We can’t wait for revolution—or god forbid, corporations—to provide us with sustainable comforts. They exist right now, in nature and in our communities: song circles and mediation groups and forests and playgrounds and plant medicines and festivals and community gardens. The revolution we crave will not come until we reconnect with those basics of human flourishing, and with ourselves.

Be well, keep up the good work, rest and find joy. I love you, we’re all in this together.

I quit academia to educate without gatekeeping. I’ve compiled a ton of free resources here. If you REALLY want to get down and dirty with that decolonial life, join my Patreοn to get access to exclusive patrons-only writing and videos, including my PhD dissertation, which was embargoed by my university for being too politically spicy. If you’re on a healing journey, you can consult with me about psychedelic use.

If you appreciate this article, please share it with others! This topic is deeply important but it makes people very uncomfortable, so it never gets as much reach as my more palatable “screw billionaires” stuff. But we need to talk about it.

Here are three ways to say thank you, and support this work:

💲 Send me a straight-up cash tip if you’re baller like that

👧 Buy my kids supplies like toothpaste and sunscreen!

Dr. Hilary Agro is an anthropologist, community organizer and mother of two young munchkins who are currently both obsessed with fart jokes.

*In this article I am not going to give in to the temptation to do an Academia and focus on the definition(s) of technology (which is about as hard to define concretely as art), and how we in the global north tend to conflate “technology” with “electronics” when it actually means, anthropologically speaking, the application of conceptual knowledge to achieve practical goals, and the tools, instruments, machines, systems, processes, and environments developed by humans to accomplish tasks, which means that shoes and forks are as much technology as the Large Hadron Collider. I find that to be a fascinating subject, especially as someone who has developed a recent interest in textiles as technology and art and the ways textiles have been devalued due to their association with feminized labour. But I have to pick up my kids in a few hours and I cannot make this article my whole-ass day. Resist, I tell myself. Stay on target.

**If anyone has come across writing from a decolonial, non-anthropocentric, Indigenous-centered worldview about how solving “problems” (using this term loosely because most of the problems modern tech purports to solve are not real and/or are actually structural things like us not having enough time or enough emotional and healing support) with plastic and electronic tech is actually fine, please link it to me. I don’t see many leftist tech nerds fighting for, or even really talking about, divesting from our reliance on electronics, or creating a movement towards local electronics recycling and manufacturing, or any other solution that would mitigate the massive environmental concerns while letting us keep our screens. But I have to optimistically assume I’m just not exposed to it. I know the tech nerds don’t like my solution (rapidly phase out the use of all plastics and electronics that aren’t 100% sustainable and 90% locally produced), so let’s go comrades, what are yours?

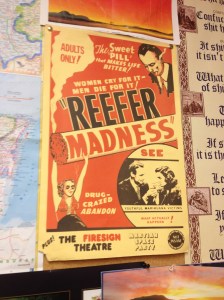

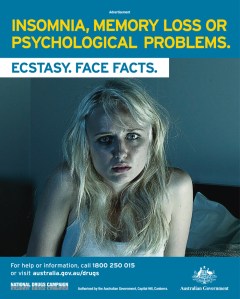

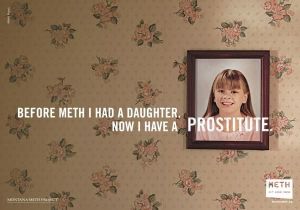

I was saved by the people at the conference, hundreds of tiny lights in a landscape of confused darkness. Activists, scholars, authors, health care workers, psychonauts, researchers, patients, libertarians, socialists. All of us bound together by the knowledge that drug prohibition is the modern day Jim Crow and the driving force behind death and destruction in the Americas. We clung to each other for sanity, sharing our successes and failures, our experiences, our self-care rituals. Every victory was tainted by the knowledge that while capitalism stands, its vultures will always find a way to profit and oppress. Marijuana is being legalized—great! But anyone with a felony record is barred from working in the legal market, meaning all the people of colour who were selling it before—shit. Companies who make ankle GPS trackers, video call systems for prisons, and opioid medications pour billions of dollars into lobbying to maintain the system the way it is, while Black and Latinx communities have their young men stolen from them and their women and children surveilled by the state through the welfare system.

I was saved by the people at the conference, hundreds of tiny lights in a landscape of confused darkness. Activists, scholars, authors, health care workers, psychonauts, researchers, patients, libertarians, socialists. All of us bound together by the knowledge that drug prohibition is the modern day Jim Crow and the driving force behind death and destruction in the Americas. We clung to each other for sanity, sharing our successes and failures, our experiences, our self-care rituals. Every victory was tainted by the knowledge that while capitalism stands, its vultures will always find a way to profit and oppress. Marijuana is being legalized—great! But anyone with a felony record is barred from working in the legal market, meaning all the people of colour who were selling it before—shit. Companies who make ankle GPS trackers, video call systems for prisons, and opioid medications pour billions of dollars into lobbying to maintain the system the way it is, while Black and Latinx communities have their young men stolen from them and their women and children surveilled by the state through the welfare system.

Sometimes, among drug policy activists, it feels like we’re the band playing on the Titanic. Sometimes it feels like maybe we can make a difference, like we’ll win. Like there’s no way we can’t win when all the evidence, and all the empathy, is on our side. But it doesn’t matter either way. We have to try. There’s just no other option.

Sometimes, among drug policy activists, it feels like we’re the band playing on the Titanic. Sometimes it feels like maybe we can make a difference, like we’ll win. Like there’s no way we can’t win when all the evidence, and all the empathy, is on our side. But it doesn’t matter either way. We have to try. There’s just no other option.

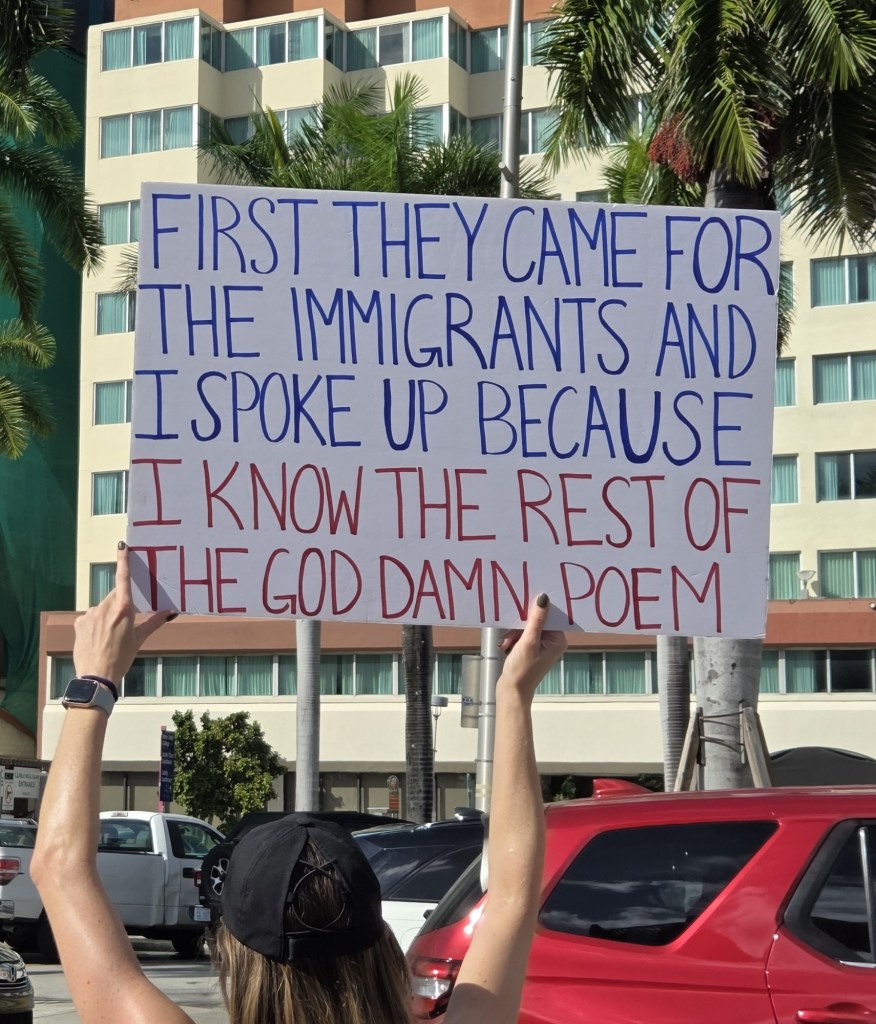

I’m not naïve: I knew all of this existed. I’ve been obsessed with American politics, how similar our two cultures seem until you scratch beneath the surface, for years. It’s not possible to be a hip-hop fan from a young age, or study the War on Drugs for a living, and avoid the global vortex of injustice and power that centres on the US. But knowing about it, and coming face to face with the sheer day-to-day mundanity of it all, are two different things. I’ve been all over the West and Northeast, where the cracks in the cultural pavement are more subtle, but touching and seeing and smelling a Southern American city for the first time, while listening to first-hand stories from around the country, poured gasoline on my deep belief that to accept conditions like this as “just the way things are” is the most dangerous possible reaction. The normalization of structural violence, white supremacy and drug prohibition allows all of it to continue, at a scale that boggles the mind. I don’t want to become complacent. I don’t want to get used to it. I don’t want to accept it.

I’m not naïve: I knew all of this existed. I’ve been obsessed with American politics, how similar our two cultures seem until you scratch beneath the surface, for years. It’s not possible to be a hip-hop fan from a young age, or study the War on Drugs for a living, and avoid the global vortex of injustice and power that centres on the US. But knowing about it, and coming face to face with the sheer day-to-day mundanity of it all, are two different things. I’ve been all over the West and Northeast, where the cracks in the cultural pavement are more subtle, but touching and seeing and smelling a Southern American city for the first time, while listening to first-hand stories from around the country, poured gasoline on my deep belief that to accept conditions like this as “just the way things are” is the most dangerous possible reaction. The normalization of structural violence, white supremacy and drug prohibition allows all of it to continue, at a scale that boggles the mind. I don’t want to become complacent. I don’t want to get used to it. I don’t want to accept it.

I’ve been texting with Mark regularly since I got back. We supported each other through our re-entry. “I was in a weird fugue state for a week when I got home,” he told me. “It felt like everything was going in slow motion.”

I’ve been texting with Mark regularly since I got back. We supported each other through our re-entry. “I was in a weird fugue state for a week when I got home,” he told me. “It felt like everything was going in slow motion.”

On the plane, I listened to Kendrick and let every word cut into me like wounds I never want to heal, wounds my soft, safe body will never actually have.

On the plane, I listened to Kendrick and let every word cut into me like wounds I never want to heal, wounds my soft, safe body will never actually have.