I am consumed by a difficult realization I’ve come to lately.

The care my children need to be as protected as possible under the conditions of capitalism outstrips my ability to provide it while also doing activism.

It’s hard to admit, but I didn’t put very much thought, before having kids, into how much doing so might take away from the activism that’s been the bedrock of my life for over a decade. Attempting to maintain the same level of productivity in my work and organizing while parenting two small children has so impacted my physical and mental health that I believe I have finally, just recently, hit extreme burnout.

My body aches at all times. My hips are in pain, possibly due to the double C-section scar that I have not given myself the time to properly heal, because who has time for that when there’s an overdose crisis and people are dying? My teeth grind at night, possibly because I have not let myself access the amount of rest I’d need to relax my body, because who has time for that when there are multiple genocides happening? The pain in my back starts at a 4 every morning and ramps up to an 8 by the end of the day, because who has time to do yoga when the oceans are acidifying and the forests are burning and leftists can’t stop angrily venting their trauma at their fellow working-class people for long enough to build a movement that can turn this ship around?

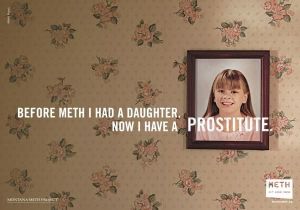

I turn this physical pain into empathy, by thinking about the parents and other workers who secretly use opioids to deal with the pain thrust upon them by the demands of capitalist (re)production. I finally get, on an embodied level, why they do it. I wish more people would understand that drug use is a rational response to a violent society, because if they did, we might stop throwing people who use drugs in prison and taking away their children. My pain turns into wisdom, and I feel compelled to share this wisdom with others, so I do. It feels so urgent. A more pressing demand than taking twenty minutes out of my day to massage my C-section scar and do physiotherapy for my diastasis recti. So the pain lingers in my body, like a poison made of urgency, of the screams of dying Palestinians and old growth forests.

I do not believe that parenting on its own is enough of a contribution to building a better world, as many people say it is. Just “raising the next generation with good values” is not enough when our land, air and water are under such dire, immediate threat that by the time my children are adults, they may not have anything left to survive with. The problems are too urgent for parents to do nothing but raise our children well. But how much labour is enough?

I made my decision to have kids before knowing that a dangerous virus would be threatening us for years on end. Before knowing how little I would be able to rely on the Canadian medical system, or any other system, or even my own community members, to protect us. I feel naive, but I see people still making the (to me, at the moment, somewhat baffling) decision to have children, so it would seem that either the gravity of the threats facing children right now are not actully as severe as they seem to be from my ostensibly well-informed perspective, or most people, even leftists, are in denial about the dangers and the weight of responsibility that comes with bringing children into the current world. Or perhaps, as a neurodivergent person in trauma recovery whose disabilities did not become so acutely obvious and pressing until after I had kids, I am simply far less equipped than most people to handle the stresses of parenting. But I’m not sure I’m so unique, as our society is disabling and trauma-creating on a scale wider than most people realize.

To keep my kids truly safe, I would need to join their school’s PTA and devote all my time to ensuring quality air filtration in their classrooms. I would need to spend the few spoons I have on teaching them to wear masks in indoor public spaces and convincing them to keep doing it, every day, even when it’s uncomfortable, even when no one else is doing it.

I would need to teach them how to garden, to build their connection to the land so they become naturalized citizens of this place, and learn to care for the land that cares for us, as well as survival skills for what may come.

I would need to prepare weekly activities that make them into good neighbours and citizens. Writing thank-you cards, preparing gifts for their friends, baking cookies to bring to parties.

I would need to expose them to Mother Earth, creatively teach them to understand and love trees so their ability to see and appreciate nature doesn’t wither under the ten-tonne weight of the cartoons and superheroes vying for their attention and filling their brains with cravings for plastic toys and refined sugar.

I have been doing some of this already. But the parts I’m able to do are already more than I have the capacity for. So where, in all of this, is there time to organize my community? How can I attend socialist meetings with an energetic three-year-old? How much of my limited supply of energy can I give to exposing myself to enough information about the various ongoing genocides that I am able to take action to stop them, without becoming incapacitated for the evening when my third labour shift of the day starts? How can I do all of this while also finishing my PhD, taking care of my relationships, and maintaining my physical and emotional health?

These are questions I have been struggling with, with no good answers. I am not currently striking a balance. Maybe when they’re older, I can more easily involve them in organizing activities. Does that mean that while they’re 3 and 5, I can take a full break from all of it? When do I start up again? Which aspects of my caregiving or my community organizing can I sacrifice?

Caring for two small children on my own, which I often do these days, means the built-in stress levels of my day-to-day are high. It requires large amounts of patience, recovery time, and practicing emotional regulation skills to parent with only sporadic community and family support. It’s easy to say “cook with your kids,” it’s harder to put that task into practice when half of your time and attention is spent intervening in messes, breaking up fights, rushing a toddler to the bathroom, and attempting to give two children 100% of your attention when at most they can each have 50%. In the evening, you have to try to do all of this while you’re already exhausted from a full day of labour, and facing down another endless bedtime (my 3-year-old Mila does not, and seemingly cannot, fall asleep until 10 pm).

And all the while, underneath, there is the gnawing tension of the knowledge that good participatory habits must be fostered early—if you wait until your kids are old enough that they’re better able to stir soup without spilling it or carry a carton of eggs without dropping it, by then they won’t want to cook with you at all, because the early flames of their desire to will have died out, tamped down by their cargivers’ exhausted impatience and redirected towards toys and screens.

Children can sense the neglect inherent to the nuclear family arrangement, and it upsets them. They need so much more than one or two caregivers can provide. My 5-year-old Eva is increasingly frustrated with my inability to read to her for as long as she would like because of the demands and interruptions of her younger sister. Meanwhile, Mila is the most extroverted human being I have ever met (you think I’m exaggerating, but I’m not) and is the easiest kid in the world if many people are around for her to interact with, but if you’re on your own with her, you do not get a break. I don’t have the energy or time for much creative play because I’m so busy meeting their basic needs and teaching them functional skills, and most of the time there are no other kids around to meet their very high need for play. It’s wonderful when they play with each other, but more often than not it ends in tears and rage as I cannot supervise closely enough to make sure Mila doesn’t grab Eva’s toys while I’m making their breakfast. Humans were not meant to live in isolation like this. It’s simply not possible to give children everything they need under these circumstances, and that’s without adding the extra pressure to stave off environmental collapse.

I do have friends who help me out, and they are lifesavers. The tiniest act—playing with my kids, washing a few dishes—fills me with overwhelming gratitude. I have especially noticed that my comrades who are the most accomodating and helpful are the ones who are the most embedded in liberationist politics, which is beautiful and, I suppose, unsurprising. The ways in which liberation-minded people are trying to live our values and build the communities we want to see gives me hope (though it also comes with complicated feelings—I cried with equal parts relief and deep guilt when my Palestinian friend offered to come vacuum my apartment when my vaccum broke, at a time when her people were and are being genocided). But these are also friends I’ve made largely through my activism—what happens if I give that up for several months, or a year, or two? Will they still show up for me if I’m burnt out and unable to reciprocate any community work? I need so much because my children need so much, and there’s so little I can offer in return right now. How much can I rely on my already overworked and burnt out friends, most of whom are BIPOC, queer, and/or disabled?

I can see, like I’m Neo at the end of the Matrix, exactly how all of these pressures create the desire to make more money. Money can solve many (though not all) of these problems, so buckling down and focusing on securing income for your own family feels like the only option. And once you do that, you’re hooked—the desire to make money in order to feel safe and afford the supports you need becomes its own self-sustaining capitalist illness. There but for the grace of my own neurodivergent stubbornness, and years of exposure to anarcho-communist principles and Indigenous ontologies, go I.

What to do, then? My bones are creaking. My mind is consumed with grief for the state of our world. It’s too much. I have recently decided to take a medical leave from my PhD to focus on getting my health back in order. I’ll be putting a pause on most of my activism as well, which will be the hardest part. But something has to change. I love myself, my kids and my comrades too much to not try to find balance. I cannot tell others that this is a marathon not a sprint, take care of yourself and all that, and not follow my own advice. I am going to reset, spend time with trees, and figure out what a sustainable work/life/activism balance looks like for me now.

Most parents in your community don’t have the ability to do this. They are drowning.

I know that many people, given how empathetic and kind my audience generally is, will want to soothe and reassure me that I’m doing the best I can. You may want to offer tips to improve my situation. I do appreciate and welcome this, but what would truly make me feel better would be if you commit to helping your comrades who have children, and talk about it publicly. You really can’t imagine how much stress they’re under. We have so normalized the idea that parenting is naturally exhausting, many parents don’t even realize that they should not have to suffer like this. Child care is mutual aid, and one of its most neglected and essential forms. I would probably cite Silvia Federici or Sophie Lewis here if any of their books existed on audiobook so I could read them, lol.

So, what can you do? Here are some suggestions:

- It’s hard to get kids out the door to go to things, so go visit your friends with kids. Ask what help they need, and if they’re unsure, the kitchen or bathroom is a great place to start. Bring food.

- The best thing for the whole family is playing with the kids themselves, as you can give parents a break while simultaneously providing something that kids badly need, which is socialization with people beyond their primary caregivers.

- Many of us parents fall into the instinct to zone out on our phones when we get a second of reprieve. If you’re offering to take care of the kids for a bit, gently ask your friend to think about what they might want to use that time for. If it’s zoning out on their phone, that’s fine, but just a little orienting question to help them be intentional about it will help, and it may make them more likely to do something more restorative with their time.

- Offer not only to go on outings with your friends and their kids, but offer to meet them at their place first to help get the kids out the door.

- Hang out with your parent friends while they’re in the park so you can chat while they kids run around the playground. Host gatherings in kid-friendly spaces.

- Talk to others in your leftist organization(s) about accomodations for parents. Can you provide engaged child care at meetings? Can you help parents get to meetings? If your group is small, can you commit to meeting at the homes of people with kids, if they’d prefer that? Can you bring snacks/food to family-friendly actions, and state that on social media so parents know they don’t have to do the added labour of packing snacks?

- Wear masks in indoor public settings. Fight for better air filtration in these same settings, or bring your own air filters to events/gatherings. Open all the windows.

Thank you, beloveds, for reading all of this, and for thinking about what I’ve offered here. Please share this post on social media so it can start discussions about these issues. Do you have similar experiences or insights to share? Am I the only one going through this?

One thing, though–note that if your instinct when you share this is to talk about how all of this is why you decided not to have kids, that’s fine, but please temper it with a stated commitment to helping other peoples’ children survive, as it can otherwise come off as dismissing these common concerns as the fault of individual parents’ decisions to have kids, when doing so is the most normal impulse in existence and shouldn’t be shamed. If we want to build a better world, we need to support parents, as they are the primary caretakers of the next generation that will help us survive in old age, and will pass on our teachings. More than anything, because children deserve so much more love and care than they are being given under the current conditions. You do too. We all do.

Hilary Agro is a community organizer, low-income PhD student & mother of two young children. If you appreciate the labour that went into this article, consider sending me and my kids some masks, HEPA filters, diapers or books, or just a cash tip ❤

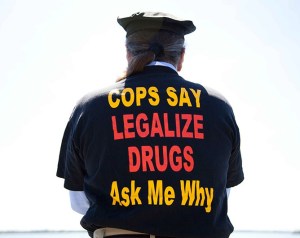

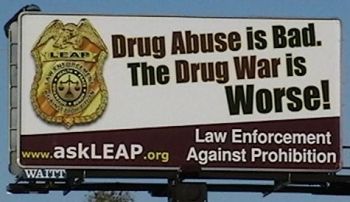

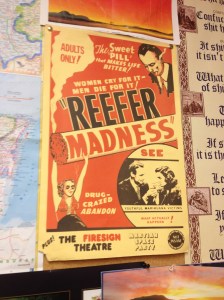

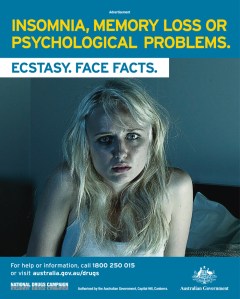

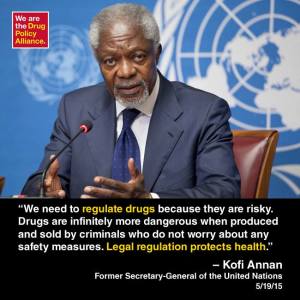

They’ve been primed by The Wire and articles about MAPS research and (at least for the young ones) their own experiences with MDMA and weed not living up to the propaganda telling them ‘one toke and you’ll die.’ OxyContin has shown that legal drugs can addict and kill, and fentanyl has shown that illegal drugs’ purity is at the mercy of the unregulated black market. Overdoses kill more people than car crashes now in North America. Over a thousand people died of opiate overdoses in Vancouver last year alone. Shit is getting real, and drug prohibition is not helping. It’s at the heart of almost all of the problems.

They’ve been primed by The Wire and articles about MAPS research and (at least for the young ones) their own experiences with MDMA and weed not living up to the propaganda telling them ‘one toke and you’ll die.’ OxyContin has shown that legal drugs can addict and kill, and fentanyl has shown that illegal drugs’ purity is at the mercy of the unregulated black market. Overdoses kill more people than car crashes now in North America. Over a thousand people died of opiate overdoses in Vancouver last year alone. Shit is getting real, and drug prohibition is not helping. It’s at the heart of almost all of the problems.